On Evaluating Cognitive Capabilities in Machines (and Other "Alien" Intelligences)

At NeurIPS 2025

I had the great honor of being invited to give a keynote lecture at NeurIPS 20251, one of the most important annual AI/machine-learning conferences. The conference took place in San Diego, in the largest conference center I have ever seen. There were close to 30,000 people registered, and walking through the halls reminded me of walking around New York City, where on the crowded sidewalks you pass by what seems to be an unending stream of humanity. But imagine if everyone you pass on the New York sidewalk were wearing a name tag, about half of them sporting affiliations of AI startup companies all named some-random-word.ai. That was NeurIPS. It was quite overwhelming.

My talk was in a huge room with a truly intimidating number of people. I found this photo of it, posted by someone online.

My talk’s (overly lengthy) title, “On the Science of ‘Alien Intelligences’: Evaluating Cognitive Capabilities in Babies, Animals, and AI",” riffed on a widely used description of LLMs as “alien intelligences.” The message was that, to understand the cognitive capabilities of today’s AI models, we should be adopting experimental methodology from the study of other “alien intelligences”: babies and animals. (Hat tip to Michael Frank’s article for this framing.)

For all my readers who weren’t at NeurIPS 2025, this post describes the main points of my talk.2

Benchmarks in AI

We’ve all seen the headlines.

In the land of AI, benchmark performance is the preferred currency.

However, while LLM-based models excel on many widely used benchmarks, it is rarely the case that a model’s benchmark performance predicts its actual capabilities in the real world. As one group of AI scholars recently wrote, “AI companies often use benchmarks to test their systems on narrow tasks but then make sweeping claims about broad capabilities like ‘reasoning’ or ‘understanding.’ This gap between testing and claims is driving misguided policy decisions and investment choices....For example, we may incorrectly conclude that if an AI system accurately solves a benchmark of International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) problems, it has reached human- expert-level mathematical reasoning. However, this capability also requires common sense, adaptability, metacognition, and much more beyond the scope of the narrow evaluation based on [mathematics] questions. Yet such overgeneralizations are common.”

There are many reasons why an AI model’s performance on benchmarks may overestimate their real-world capabilities. These can include (among other issues):

Data contamination: Questions or problems from a particular benchmark may have been included in the model’s training data. This seems to happen rather frequently.

Approximate retrieval: A term coined by Subbarao Kambhampati, meaning that LLM-based systems don’t have to have been trained on the exact text of a question, but can interpolate the answer from similar questions and answers in the training data, without having the more general capability the benchmark is intended to assess.

Exploitable spurious associations or “shortcuts”: In many cases, AI systems have been found to exploit unintended associations in benchmark data in order to give “the right answer for the wrong reason”.3 I’ll discuss examples of this phenomenon from my own research later in this post.

No testing for consistency, robustness, generalization, or mechanism: In almost all cases, studies reporting AI performance on benchmarks report only accuracy on the specific benchmark, and do not carry out tests for consistency (how often does the system give the same answer if the prompt is repeated?), robustness (is the system’s performance robust to variations in the questions or problems that would not affect humans’ answers?), generalization (does the system’s performance generalize to other benchmarks that attempt to evaluate the same capacities?), or mechanism (how is the AI system solving the benchmark tasks?).

Lack of construct validity: A test has “construct validity” (a technical term in psychology) if it accurately measures the more general ability it is intended to measure. For example, “analogical reasoning ability” is a “construct”, and a benchmark for analogical reasoning has construct validity to the extent that performance on that benchmark predicts the more general ability. The fact that most AI benchmarks don’t do a good job of predicting performance in the real world means that they lack construct validity.

Anthropomorphic assumptions: Some AI evaluations adapt (or directly use) tests designed to evaluate human cognitive capacities and give them to AI systems (E.g., IQ tests, SAT, medical licensing exams). However, even if the test has reasonably good construct validity for humans, these tests often make assumptions that are not valid for AI systems, which are built on very unhuman-like mechanisms (e.g., abilities for memorization, approximate retrieval or shortcut exploitation.)

Evaluation Principles from Cognitive Science

Many of the issues I sketched above also arise in assessing cognitive capabilities of humans and other biological intelligences. In particular, the issue of anthropomorphic assumptions has long been a problem for comparative psychology—the study of cognition in nonhuman animals—and assumptions related to adult human intelligence have been an issue for developmental psychology—the study of cognition in babies and young children.

These disciplines have developed experimental methodologies to help deal with such issues. As developmentalist Michael Frank wrote, “Imagine first contact with an alien intelligence. A scientist might ask, do the aliens have the same concepts as humans? Do they understand other minds? Can they reason about cause and effect? Developmental psychologists have been asking such questions for years about another kind of alien intelligence: human children. Methods from this research can help researchers probe the capacities of LLMs.” Frank’s essay “Baby steps in evaluating the capacities of large language models” discusses such methods.

Related papers laying out evaluation principles from cognitive science include Rane et al.’s “Principles of animal cognition for LLM evaluations: A case study on transitive inference”, Ivanova’s “How to evaluate the cognitive abilities of LLMs” (preprint version here), and Voudouris et al.’s “Bringing comparative cognition approaches to AI systems”.

Below I summarize (and add to) these cognitive-science-inspired principles of evaluation, and illustrate their use in case studies from both psychology and AI research.

Six Principles for More Rigorous Evaluation of Cognitive Capacities

Principle 1: Be aware of your own anthropomorphic cognitive biases.

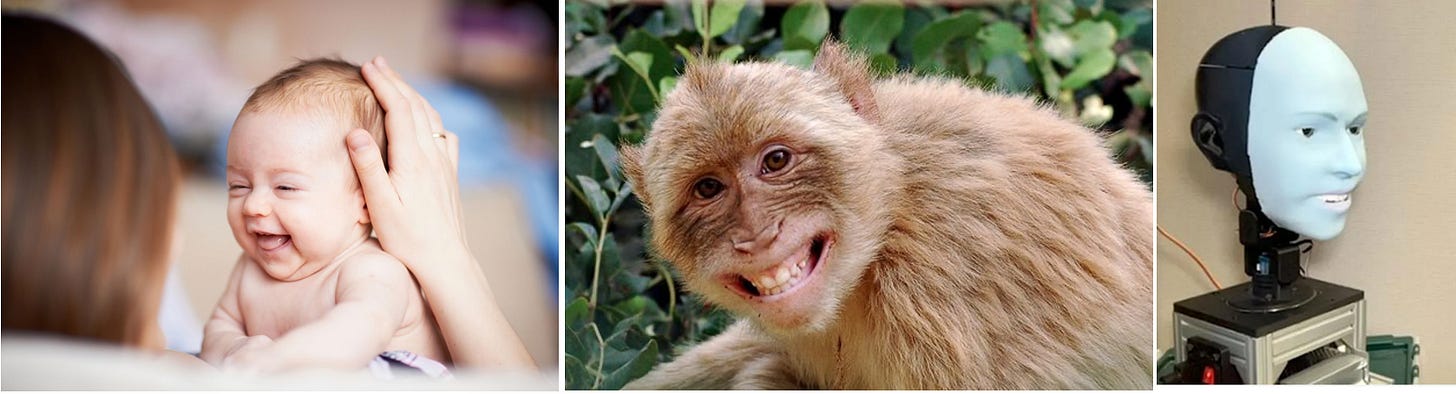

Consider these three photos:

At first glance, it looks like they feature a happy baby, happy monkey, and happy robot. While the smile on the baby likely reflects happiness, it turns out that this expression in monkeys signifies not happiness but terror. And for the robot, the smile reflects not an internal human-like emotion but a programmed set of actuator functions in response to a classification of a human facial expression.

Our immediate, unconscious response to these photos illustrates the human propensity to project human-like attributes—emotion, beliefs, intentions, and abilities—onto babies, nonhuman animals, and machines. In the case of chatbots, this is the well-known Eliza effect. This human cognitive bias can lead any of us, scientists included, astray in evaluating cognitive capabilities. We might assume that a pet dog understands human emotions or that a linguistically fluent LLM can be usefully assessed by a standardized exam designed for humans. To perform more rigorous evaluations, scientists need to be consciously aware of their anthropomorphic biases.

Principle 2: Be skeptical of others’ (and your own) hypotheses. Design control experiments for possible alternate strategies that could produce the observed behavior.

This is perhaps the most important principle, but one largely ignored in AI evaluation. Here I’ll give two case studies from psychology illustrating how this principle has been applied.

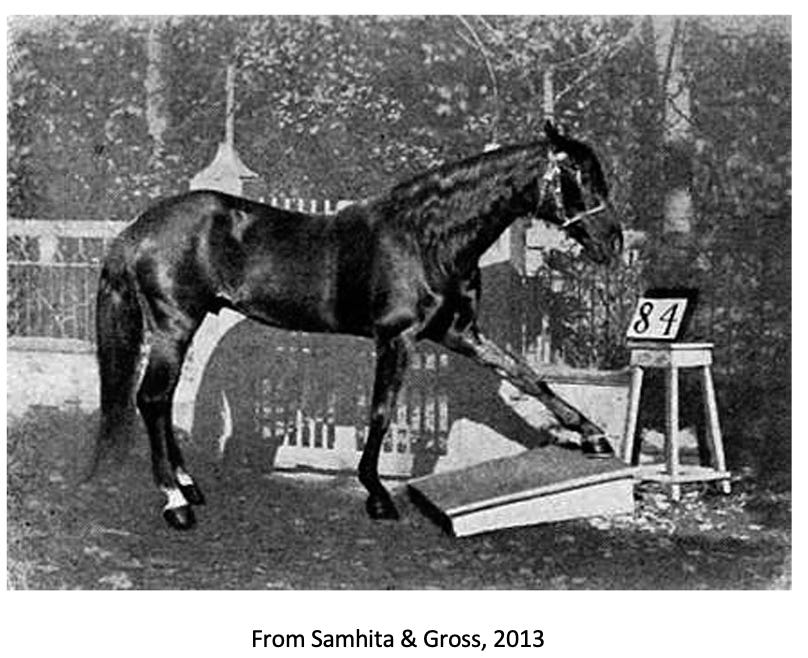

Case study: Clever Hans

Clever Hans was a horse in turn-of-the-20th-century Germany who was hailed in 1904 as “the first thinking animal.” Hans could perform all kinds of feats, including solving arithmetic problems, reading a clock, recognizing playing cards, and identifying the composer of a piece of music. To answer a question, the horse would tap his hooves to signify a number or a multiple-choice option.

According to Samhita & Gross’s history, observers at first assumed that the horse’s abilities were a hoax, with the horse’s trainer somehow providing Clever Hans with the answers. However, it was shown that Hans could perform his feats even when his trainer was absent. The German board of language carried out a study in 1904 that concluded that Hans’ abilities were genuine, and “the majority of biologists, psychologists, and medical doctors, experts of all kind, and laymen were rather convinced by this example that animals are able to think in a human way.”

It took four years and several careful control experiments by the psychologist Oscar Pfungst to finally figure out, in 1907, what was going on. Among other things, Pfungst showed that Clever Hans could not answer the question if the questioner did not know the answer, or if he could not see the face of the questioner. Pfugst concluded that the horse did not, in fact, have the claimed capacities for counting, arithmetic, card reading, and so on. But Hans was a genius at something much more useful for a horse: the social ability to read the questioner’s subtle facial expressions in order to know when to stop tapping. These revealing facial expressions did not seem to be under the questioner’s conscious control; even when Pfungst tried to suppress them, the horse was still able to read his face to give correct answers.

Pfungst’s skepticism of a previously accepted hypothesis (”Clever Hans was able to think in a human way”) and design of careful control experiments to “adversarially” test the hypothesis are essential skills that are now emphasized in the training of comparative and developmental psychologists.

Another case study: Human infants’ preference of prosocial behavior

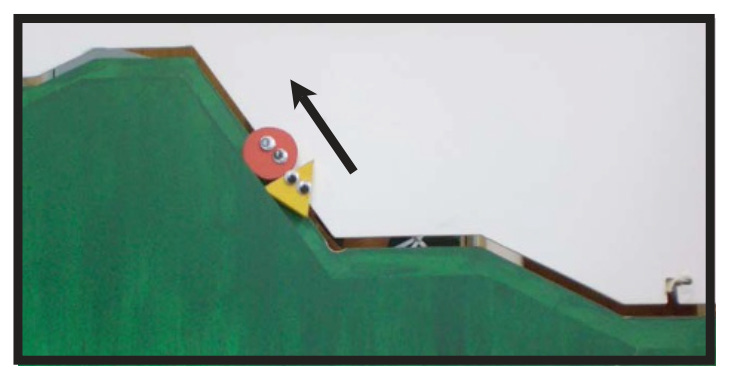

A second case study involves the hypothesis that infants can distinguish positive and negative social actions, and prefer positive ones.

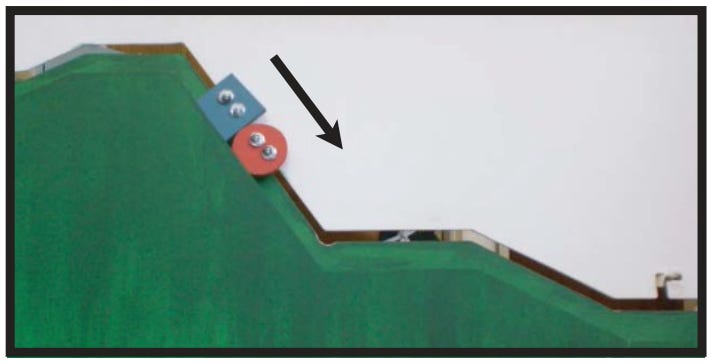

A 2007 paper, “Social evaluation by preverbal infants”, reported on a experiments testing the hypothesis that “preverbal infants assess individuals on the basis of their behaviour towards others,” and that infants as young as six-months old prefer individuals that exhibit helpful social behavior. The experiments involved infants viewing puppets—wooden shapes with googly eyes—playing out simple episodes. In the first episode, a circle shape (”the climber”) starts out at the bottom of a hill, tries to climb uphill a few times and fails, sliding down until a triangle shape (”the helper”) appears at the bottom of the hill and moves up, pushing the circle up to the top of the hill:

In the second episode, the climber again tries to climb the hill, failing in the same way as in the first episode, but here, instead of a helper, a square shape (“the hinderer”) appears from the top of the hill and pushes the climber down to the bottom of the hill.

After viewing both episodes, infants were encouraged to reach for either the helper or hinderer puppet. In almost all runs of the experiment, infants reached for the helper. The authors also performed several control experiments to see if this preference was due to “perceptual” rather than “social” factors, such as preferring upward to downward motion, or animate vs. inanimate objects. They found that in the control experiments, infants did not show a clear preference for helper or hinderer. The authors interpreted these results as supporting their hypothesis that nonverbal infants prefer those who exhibit prosocial versus antisocial behavior.

However, it turns out there are alternative possible explanations for the infants’ choices. In 2012, another group published a reexamination of the 2007 infant-preference experiments. This second group, with lead author D. Scarf, noticed that in the original “helper” episodes, the climber briefly bounced up and down when it got to the top of the hill. There was no bouncing in the hinderer episodes. Was the infants’ preference for the helper due to enjoying the bouncing (a perceptual feature) rather than recognizing the helping (a more abstract concept, resulting from social reasoning)?

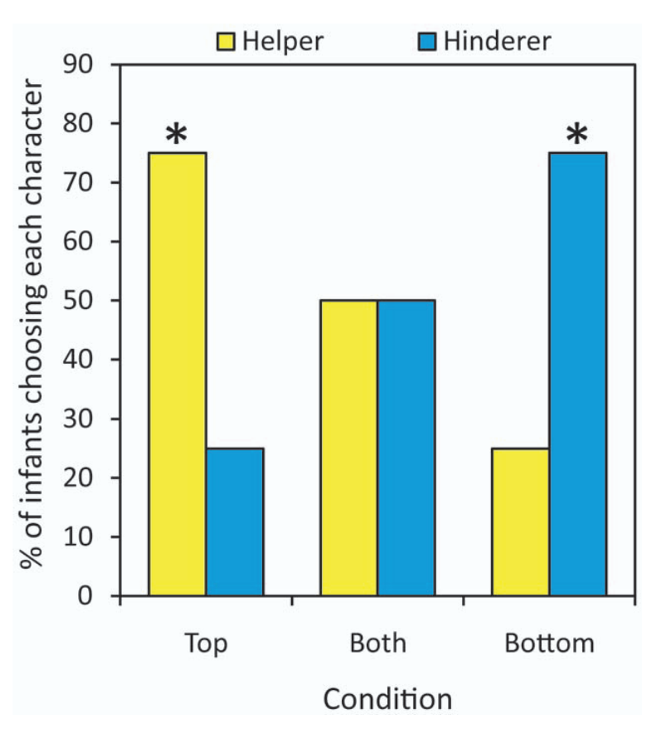

Scarf et al. recreated the puppets-on-a-hill scene, and ran experiments with three conditions: (1) Top: the climber bounces only at the top on helper episodes (as in the original experiments); (2) Bottom: the climber bounces at the bottom only on hinderer episodes; (3) the climber bounces at the top on helper episodes and at the bottom on hinderer episodes.

After each of these trials, the experimenters recorded which character infants reached for. Here are the results:

In summary, this study seemed to counter the original study’s hypothesis: infants’ preferences for helper or hinderer seem to depend on which episodes featured the climber bouncing, not on whether an episode featured helping or hindering. When the climber bounced on both episodes, infants’ preference was 50-50.

Unsurprisingly, the debate did not stop there. In 2015, the original paper’s first author, J. K. Hamlin, shot back with a paper describing yet another set of experiments that challenged Scarf et al.’s results; these experiments indicated that subtle differences in Scarf et al.’s helper and hinderer scenarios might have prevented infants from recognizing the climber’s actions as “goal oriented”. Then in 2024 a third group of researchers published results from a large-scale replication of the original study with many more infants, across 37 different labs. In this larger study, there was no significant difference seen between infants’ choice of helper and hinderer—a strong negative result for the original hypothesis. As far as I know, this is where things stand today.

I chose this case study not to make claims about infants’ social reasoning abilities, but because it is a good example of the kind of “adversarial” experimental iteration that goes on in the developmental (as well as comparative) psychology community. At each iteration, researchers are skeptical of others’ (or their own) hypothesis and devise control experiments to test alternative strategies that could produce the observed behavior.

This kind of back-and-forth of experimenting and publishing, which in this case took place over many years, is common in psychology but unfortunately rare in evaluations of AI systems. I believe that such a dynamic is essential for progress in science. It’s not an easy task. As one developmentalist pointed out, “The study of infant cognition requires a high level of creativity in the creation and testing of alternative explanations.” The same could be said for the study of animal cognition and machine cognition, and the latter field shows too little of this kind of creativity in devising control experiments for testing AI.

Principle 3: Design novel variations of stimuli or benchmark items to test robustness and generalization.

The most common approach for evaluating a cognitive capability in an AI model is to use an existing benchmark or test (or devise a new one) that is purported to measure that capability, run the AI model on that benchmark or test and report the accuracy. I discussed several problems with this approach earlier in this essay. In both comparative and developmental psychology, it is common to design variations on experimental stimuli to establish robustness of a particular capability, and fortunately, this is becoming a more common practice in AI evaluation as well.

An example from my own work is on evaluating the robustness of analogical reasoning in LLMs. A 2023 paper, “Emergent Analogical Reasoning in Large Language Models” showed that OpenAI’s GPT-3 surpassed (or in one case, came close to) human accuracy on four benchmarks for analogical reasoning. My collaborator Martha Lewis and I investigated the robustness of GPT-3 and later GPT models by creating and testing these models on several kinds of variations on the original benchmark items, ones that should not affect a system that can robustly make analogies. For example, one of the original benchmarks consisted of “letter-string analogies,” such as “If the string abc changes to the string abd, what is the analogous change to the string pqrs?” We created two kinds of variations on these problems, in which a “counterfactual” alphabet is specified, and the solver is asked to solve the problem given the counterfactual alphabet. The first kind of counterfactual alphabet is one in which the order of some letters is permuted; the second kind is one in which non-letter symbols (e.g., % or &) replace letters. We found that while humans are able to solve these variants about as well as the original problems, the GPT models we tested were substantially worse. We similarly investigated robustness by creating variants on other benchmarks used in the original paper (digit-matrix problems and story analogies) and in most cases saw a similar pattern: humans were substantially more robust to variations than GPT models. In short, to assess general abilities, it is essential to evaluate systems not only for accuracy on a given benchmark but also for robustness to variations.

Principle 4: Be curious about mechanisms underlying performance.

Something that baffles me about many AI researchers is the seeming lack of curiosity about the mechanisms underlying the benchmark performance they report. It’s true that the mechanisms behind LLM responses (and those of other complex AI models) can be hard to figure out, and the field of “mechanistic interpretability” is still in its infancy. But there are often ways that the behavior of a system can give clues to the underlying mechanisms.

An example from cognitive science is understanding how children, chimps, or other “higher” biological intelligences represent numbers. For example, many young children learn to recognize numbers and count before they have any understanding of what the numbers mean as quantities or the relationships between these quantities. While little is still known about the detailed neural mechanisms of such representations, developmental psychologists have come up with many types of behavioral experiments that give insight into the mental representations of numbers and how these representations develop in children over time. There is a similarly rich literature on investigating the representations of numbers in chimps and other primates, and in corvids and other birds.

In a previous post here, I wrote about my own group’s investigation into the mechanisms underlying large reasoning models’ success on the “Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus” (ARC), a prominent benchmark meant to test few-shot abstraction and analogy. According to its creator, Francois Chollet, ARC is “built upon an explicit set of priors designed to be as close as possible to innate human priors…ARC can be used to measure a human-like form of general fluid intelligence and that it enables fair general intelligence comparisons between AI systems and humans.”

The “innate human priors” Chollet is referring to are the core-knowledge systems proposed by the psychologist Elizabeth Spelke and her collaborators. These include concepts related to: objectness: knowledge that the world can be parsed into objects that have certain physical properties, such as traveling in continuous trajectories, being preserved through time, and interacting upon contact; numerosity: knowledge of small quantities and notions of smallest, largest, greater than, less than, etc.; and basic notions of space, geometry, and topology: knowledge of lines, simple shapes, symmetries, containment, etc. Whether such concepts are “innate” in humans, as claimed by Chollet (following Spelke), or learned during development, is controversial, but clearly such concepts are part of humans’ fundamental conceptual repertoire.

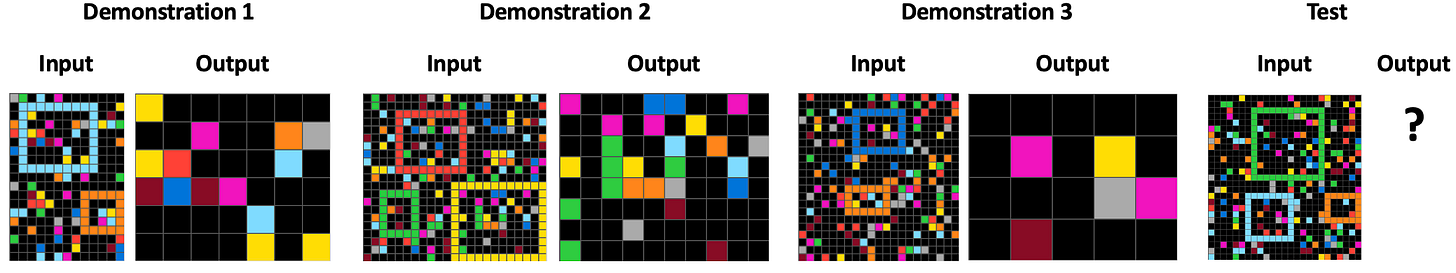

Here’s a sample task from ARC, which features three demonstrations—examples of input and output grids—and a test input:

The task of the solver is to generate a new grid that applies the same transformation rule that governs the demonstrations. Here that rule is something like “extract the subgrid contained in the largest rectangle.”

Chollet designed 1,000 puzzles of this sort (some much more difficult than this one), published 800, and kept 200 carefully guarded to use in “private” evaluation sets. One private evaluation set was used to test entries in the annual “ARC Prize” contest, which in 2024 offered $600,000 for a program that achieved 84% or higher accuracy on the evaluation set of 100 tasks. While none of the contest entries achieved this threshold, soon after the competition, a pre-release version of OpenAI’s o3 “reasoning model” got a whopping 87.5% accuracy on a new, 100-task “semi-private evaluation set” designed by Chollet to evaluate commercial models like o3 whose compute needs exceeded the limits set in the official competition. And o3’s compute needs were high: the total compute cost was estimated to be close to $5,000 per task.

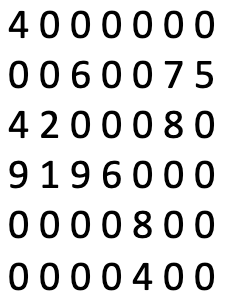

It should be noted that all of the successful AI approaches on ARC require a text-based input, in which colors are translated into numbers, and each grid is given as an array of these numbers. The code is: 0-black, 1-blue, 2-red, 3-green, 4-yellow, 5-gray, 6-magenta, 7-orange, 8-cyan (light blue), and 9-brown.

For example, here is the way an AI model would be given Demonstration 1’s output grid, where numbers code for colors:

The number-color encodings are meant to be arbitrary, and the assumption is that an AI model should be able to recognize patterns among the numbers in a similar way to which humans recognize numbers among the corresponding colors. (As I’ll explain below, it doesn’t quite turn out that way.)

This kind of text encoding is used because none of the current multimodal AI models has been able to achieve high performance on image inputs for ARC. They do much better using these text-based inputs.

While o3 gets high accuracy on ARC, what does this say about its general capacities for robust abstract reasoning? Has it captured the kind of humanlike abstraction and combination of core-knowledge concepts that ARC was meant to evaluate?

Our group tested o3, along with two other state-of-the-art large reasoning models, and humans on a simpler version of ARC called “ConceptARC”, in which each task focused on a particular basic concept, such as “horizontal / vertical” and “inside / outside”. (Our paper is here.) We used the same text-based representation and prompt as in the other o3 ARC evaluations, but in addition to asking each model to generate an output grid, we also asked it to give a natural-language description of the transition rule that governs the demonstrations and is applied to generate the output grid.

We found that on the tasks for which the AI models produced a correct output grid, the rule they stated was correct (as intended by the task creator) about 70% of the time. The other 30% of the time they stated either incorrect rules—ones that don’t correctly match the demonstrations—or “correct but unintended” rules—ones that match the demonstrations but don’t capture the intended core concept in the task. On the other hand, when humans got the output correct, they stated the intended rule about 90% of the time.

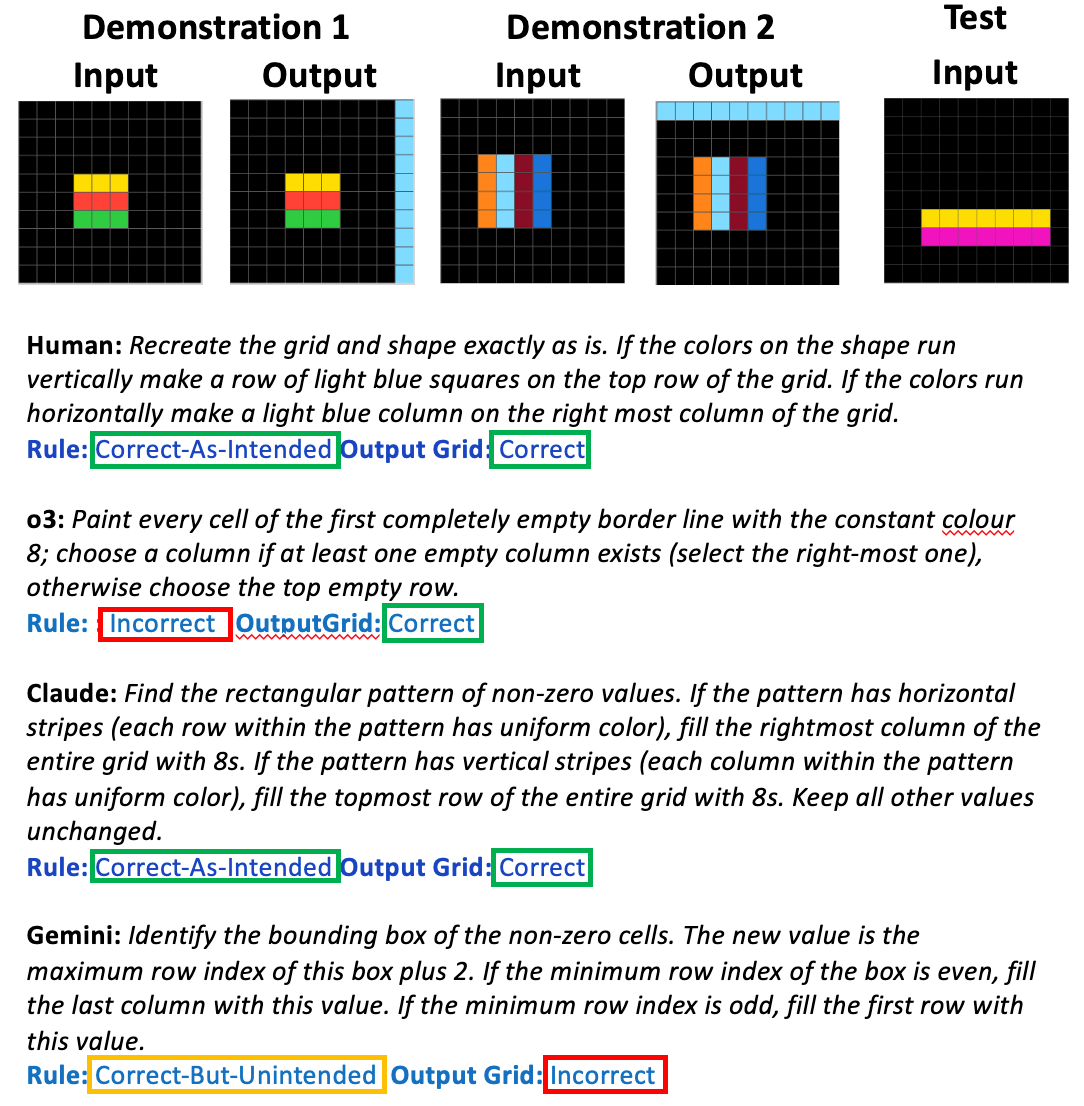

Here are some examples of rules generated by humans and models for sample ConceptARC task. Try to solve the task and come up with your own rule before reading the human- and model-generated rules. (Recall that for AI models, 8 encodes cyan (light blue).)

In our study, humans were overwhelmingly likely to conceptualize the task as concerning horizontal and vertical orientations. Here, Claude generates a human-like rule, while o3 and Gemini ignore orientation (and the notion of objects) altogether. o3’s rule is incorrect in describing the demonstrations, but that rule by chance yields a correct output grid. Gemini focuses on numerical properties of the integers used as codes for colors—a feature intended to be irrelevant, and unavailable to humans using a visual representation—and while its rule fits the demonstrations, its generated grid is incorrect.

Most often, we found that the features used in both “correct but unintended” and “incorrect” rules were less abstract—that is, more closely tied to the specifics of ARC tasks, such as grids, individual colors, or properties of the numbers used to encode them, than to the “core knowledge” concepts the tasks were meant to capture. For this reason, we argued that evaluation based only on accuracy scores, which is generally how ARC evaluations are done, may overestimate the ability of these models to perform more general abstract reasoning. The “why and how” matters; insight into the alignment between human and AI “understanding” is essential for predicting how these systems will generalize their abilities in the human world.

It’s important to ask why we think that the rules generated by these AI models are causally related to the generated output grids. We found that each model’s generated rule for a given task, whether correct, unintended, or incorrect, almost always faithfully described that model’s generated output grid, correct or not, giving evidence that the generated rules are faithful to the process of generating an output grid.

The principle I’m illustrating with this example asks researchers to be curious about “mechanisms.” Stated rules (or other self-reports on behavior), to the extent that they are faithful to the answers, are only a first approximation to a more detailed answer “why did the model or human give that answer,” but even such a rough approximation can yield insight that is masked by looking at accuracy alone.

Principle 5: Consider performance vs. competence.

The performance vs. competence distinction has long been proposed as important for understanding cognitive capacities in biological intelligence, and more recently in comparisons between humans and AI systems. The question is, does the system possess the capacity under study (competence) but cannot demonstrate it due to unrelated task requirements (performance)?

A classic example from developmental psychology concerns experiments on “object permanence” in infants. The famous psychologist Jean Piaget argued that before about nine months of age, infants don’t understand that objects that disappear from view (e.g., move behind a screen) still exist, even though they are unseen. His argument was based on the observation that prior to a certain age, infants don’t search for objects that are fully hidden, such as a toy that is covered with a cloth. However, many more recent developmentalists have argued that infants do indeed understand object permanency much earlier than 9 months, and their lack of searching for hidden objects is a performance, rather than competence issue. It may be that young infants are limited in short-term memory, so they forget to search for the object, or that they unable to coordinate the multiple actions needed to search and obtain the hidden object.4

In the context of AI, a 2024 paper by Hu and Frank showed that while several relatively small language models had the competence for grammaticality judgment based on the models’ assigned log probabilities, they were not able to perform well on a grammaticality-judgment task due to “auxiliary task demands” unrelated to grammaticality judgment.

Another example comes from the study I described above on ConceptARC. In addition to our experiments with textual inputs (using numbers to code for colors), we looked at the multimodal abilities of o3, Claude, and Gemini to perform ConceptARC tasks using visual inputs. While these models are all quite bad at solving these tasks in the visual modality, we found that in some cases, they were able to state the correct and intended rule (i.e., showing competence at abstract reasoning) but not to apply it correctly due to unrelated visual problems, such as determining grid dimensions from images (i.e., failure due to performance issues).

In summary, looking only at the accuracy (performance) of an individual, human or machine on a given task can result in overestimating general competence, e.g., when AI models get the right answer for the wrong reason in solving ConceptARC tasks, or it can result in underestimating general competence, e.g., when AI models generate correct-as-intended rules but cannot carry them out due to unrelated perceptual limitations. It is essential for evaluations to go beyond simple accuracy measures, and to look into mechanisms as well as possible constraints on performance.

Principle 6: Analyze failure types, and embrace “negative” results.

You test your favorite AI model on your favorite benchmark. It gets 88% accuracy. Pretty good, right? But what could give you more insight on what’s going on? This last principle says that one of the best things you can do is look at the 12% of items that your model got wrong. Analyzing the types of errors made by a system can be one of the best ways to get insight into how the model works. More people in AI should include error analysis in their reporting of benchmark results.

Collecting and analyzing human errors is an entire subfield of cognitive science, one that has provided a huge amount of insight into mechanisms of various cognitive processes. AI researchers should follow suit, and be as curious about the errors a system makes as about its successes.

One example of such error analysis in AI was reported in a paper with the evocative title “Embers of autoregression show how large language models are shaped by the problem they are trained to solve”. This paper showed that some of the puzzling errors made by AI models (GPT-4 in this case) could be explained by the biases these models acquire as part of their training to predict the next token in a sequence (such training is technically called “autoregression”). For example, GPT-4 is more likely to make errors on a task whose correct output tokens were less likely to be seen in the training data than on a completely equivalent task with more likely output tokens. The paper shows that such models retain this kind of trace (“ember”) of their training process, sort of like a modern human retaining biases formed in early evolution.

In addition to paying more attention to failures, this principle urges scientists to embrace so-called “negative results.” If you’ve done a careful study and your initial hypothesis is not verified, this could be an important result in and of itself. One of my earliest experiences in the field of genetic algorithms was working with a fellow graduate student on designing a computer experiment meant to validate a widely published hypothesis proposed by our advisor; we found that the hypothesis was not supported. Rather than putting all the data and result files in a back drawer and going on to something else, we dug in further and managed to publish a whole series of papers about why the failure occurred and what the original hypothesis lacked.5 I had a similar experience when I was a postdoc, and attempted a replication of a study from one of my scientific heroes, finding that I could not replicate his results. Again, embracing this negative result led to some of the most impactful work of my career.6

There’s definitely a publication bias against negative results. One comparative psychologist lamented the bias against “killjoy explanations”—ones that pop the bubble of exciting-sounding phenomena. I think the same sentiment shows up in “killjoy” AI explanations; the authors of such papers (including myself) often get the pejorative status of “AI skeptics” or “AI deniers,” and are assured that our negative results are not worth publishing, since AI is improving so fast. It’s hard to do science when skepticism is considered to be bad and speculation about the future is used to reject current fact-based studies.

Conclusion

Bringing all the principles together:

Principle 1: Be aware of your own anthropomorphic cognitive biases.

Principle 2: Be skeptical of others’ (and your own) hypotheses. Design control experiments for possible alternate strategies that could produce the observed behavior.

Principle 3: Design novel variations of stimuli or benchmark items to test robustness and generalization.

Principle 4: Be curious about mechanisms underlying performance.

Principle 5: Consider performance versus competence.

Principle 6: Analyze failure types, and embrace “negative” results.

All of these principles encourage replicating and building on others’ results, as well as revisiting and iterating on your own results. Unfortunately, the culture of AI conferences (where most work is published) often looks down on such iteration, calling it “incremental”, and “lacking novelty”—both terms being the kiss of death from a reviewer. Conversely, I would argue that the replication of prior findings and the “incremental” extension of prior work is essential for the progress of science.

To bring back the question about modern AI models from Terrence Sejnowski at the beginning of this post: “Some aspects of their behavior appear to be intelligent, but if it’s not human intelligence, what is the nature of their intelligence?” I hope I have communicated here that determining the nature of “alien” intelligences such as animals, children, and machines requires substantial rigor and creativity. We need more of this rigor and creativity in AI evaluations. And, amidst the push for ever more difficult benchmarks, I would propose that, rather than harder benchmarks, we need more rigorous evaluation methods.

In case you were wondering, “NeurIPS” is short for “Neural Information Processing Systems”.

See, e.g., Geirhos et al, “Shortcut learning in deep neural networks”.

See, e.g., Baillargeon, Spelke, and Wasserman, “Object permanence in five-month-old infants”.

E.g., Mitchell, Holland, and Forrest (1994). “When will a genetic algorithm outperform hill climbing?”

Mitchell, Crutchfield, and Das (1996). “Evolving cellular automata to perform computations: A review of recent work”.

Great article. I posit that reluctance to try to reproduce results and examine failure is why true progress in AI research gets sidelined in favor of the elusive search for clever new ways to hack benchmarks. There is no percentage in asking, "Did this model get the correct results for the wrong reasons," if you work for one of the frontier labs. It's a common-sense question and over a beer, I'm sure a lot of researchers would agree it's a worthwhile thought experiment. In practice, you'd find research teams reluctant to carry it out, precisely BECAUSE of the notion that everything is moving so fast, which is to say, a culture of manic FOMO, they don't want to be slowed down by what they'd frame as "side issues," when those systemic eval flaws are actually central to ongoing performance failure. IMO, one reason frontier labs avoid digging into failure modes too much is it will point to architecture issues that are not easily fixed. All of which comes down to the old saying, "It is hard to get somebody to understand something (e.g. the need for curiosity abt both success and failure) when his job depends on NOT understanding it. Also suspect the data contamination that quite conveniently allows models to score higher on benchmarks is not accidental, but a kind of contamination that is avidly sought for training data. Meta admitted as much.

I always enjoy your articles. This is a great read and the recorded keynote presentation is wonderful to watch.

I remember from your 2019 book a fantastic chapter called "Metaphors We Live By," which you cited was based on the eponymous book by Lakoff & Johnson from 1980. They say at the beginning of their book that "argument is war" metaphor can also be changed to a different metaphor: "argument is a dance."

So regarding your sixth principle and trying to promote publication of more negative results - I wonder if we need a new metaphor to fundamentally change the discussion?

It seems to me that the singular focus on novelty and positive results in the science publication industry is a version of the "argument is war" metaphor. But real progress only happens, as you point out, when we have a figurative situation where "argument is a dance."

Just thinking out loud :) Anyway, thanks for your great writing!

Cheers.